Stumbling Stones - Stolpersteine - Pavés de mémoire

Pavés de mémoire/Stolpersteine/Stumpling Stones Bruxelles

https://bx1.be/news/woluwe-saint-pierre-15-paves-memoire-victimes-de-rafle-12-juin-1943-inaugures/#.WyPNLUKmZh9.email

Woluwe-Saint-Pierre : 15 pavés en mémoire des victimes de la rafle du 12 juin 1943 inaugurés

The artist Felix Nussbaum

Adolphe Nysenholc

Short film on Adolphe Nysehholc

His parents' Stolpersteine in Brussels

Michael Birkenmaier's presentation and research on their son, Adolphe who was hidden and saved by a family in Ganshoren just outside Brussels from 1942 to the end of the war:

https://drive.google.com/open?id=19HbOIIu1Red84CJ6F9GwIFRQg0Kyzl6X

https://bx1.be/news/woluwe-saint-pierre-15-paves-memoire-victimes-de-rafle-12-juin-1943-inaugures/#.WyPNLUKmZh9.email

Woluwe-Saint-Pierre : 15 pavés en mémoire des victimes de la rafle du 12 juin 1943 inaugurés

Devant le n°10 de la rue André Fauchille à Woluwe-Saint-Pierre, si l’on baisse le regard, on peut désormais apercevoir 15 pavés dorés. Des pavés, inaugurés le samedi 12 juin, qui commémorent le 75ème anniversaire de la rafle de 12 enfants juifs cachés à l’internat du Lycée Gatti de Gamont, de sa directrice et de son mari ainsi que de leur fille.

Emma Patron, Andrée Ovart ou encore Rachel Tomar : leurs noms sont désormais gravés dans la pierre pour ne pas les oublier. Le 12 juin 1943 à 4 heure du matin, la Gestapo allemande faisait irruption dans le Lycée Gatti de Gamond et emmenait avec elle 15 personnes dont 12 enfants. Seuls deux jeunes et un adulte survivront.

Depuis le lundi 12 juin, des pavés en or ont été placé rue André Fauchille pour se souvenir de ce drame. 200 personnes dont des membres des familles des victimes étaient présentes lors de l’inauguration. Madame l’ambassadeur d’Israël, un représentant de l’ambassade d’Allemagne et de l’Association pour la Mémoire de la Shoah faisaient également partie des invités.

13 juin 2018

His Stolpersein and that of his wife's in Brussels

Felix Nussbaum

In letters he wrote during his forced exile in Scandinavia, the German playwright Bertholt Brecht complained about the sobriquet applied to people like him, who had decided to leave Germany upon the Nazi accession to power. “The name they coined us – emigrants - is fundamentally erroneous, since this was not a voluntary migration for the purpose of finding an alternative place to settle. The emigrants found themselves not a new homeland but a place of refuge in exile until the storm passes - Deportees that’s what we are, outcasts.”

The fate of artist Felix Nussbaum’s family, from Osnabrueck, Germany, substantiates the desperate efforts to find shelter and refuge on foreign soil. It is the history of one family among many that found itself in the maelstrom of hopeless flight.

Philip Nussbaum, Felix’s father, was a proud German patriot who belonged to the organization of World War I veterans. When the new regime came to power, he had to surrender his membership. In his parting remarks, he said, “... for the last time, dear comrades in arms, I salute you as a loyal soldier... And if again I am called to the flag, I am ready and willing.”

At that time, his son, the artist Felix, was in Rome with a small group of German students at an extension of the Berlin Academy of the Arts, after winning a prestigious scholarship. In April 1933, Goebbels, Hitler’s Minister of Propaganda, visited the artistic elite and lectured them on the Fuhrer’s artistic doctrine. “The Aryan race and heroism are the main themes that the Nazi artist is to develop.” Felix understood that there was no place for him, as an artist and a Jew, within the confines of this doctrine. He left Rome by early May and his scholarship was revoked a short time later. In his work, The Great Disaster, 1939, he expressed his intuition concerning the dramatic change that Hitler’s accession had wrought - the destruction of Europe and of Western civilization.

Felix’s parents, Philip and Rachel, left Osnabrueck, as did many Jewish inhabitants of this town. His older brother, Justus, and his family remained to run the family’s thriving metal business. After a brief stay in Switzerland, Felix’s parents traveled south to meet with their beloved son in Rapallo, a fishing town on the Italian Riviera. The sunshine and the ambiance of the place eclipsed the clouds of war, and the Nussbaums spent the summer of 1934 together, in what would be Felix’s last encounter with his parents. His uplifted mood is expressed in the joyous, carefree colors of his works during this time, e.g., The Beach at Rapallo, 1934.

In 1935, his parents succumbed to their nostalgia for Germany and expressed their wish to return to their homeland, despite the fierce objections of their son, Felix, who rewrote the last line in his father’s parting poem: “... and if again I am called to the flag, I will desert to a far away place for sure.” It was the only time he objected to the views of his father, his source of spiritual and economic support.

The family members parted ways. Felix and his life partner, Felka Platek decided not to return to Germany. They first went to Paris in January 1935 and then to the Belgian resort town of Ostende. Several months later, they moved in with friends in Brussels. There, in October 1937, they married. Felix’s brother Justus, was forced to emigrate in 1937 when all Jewish businesses in Osnabrueck were Aryanized. Justus, his wife, and their two-year-old daughter, Marianne, fled to the Netherlands on 2 July of that year. There, together with several additional forced migrants, he managed to establish a scrap-metal company.

In the meantime, the situation in Germany was deteriorating. On Kristallnacht, the synagogue in Osnabrueck was torched, Jewish homes were looted, and all Jewish men were taken to Dachau. In May 1939, Felix’s parents decided to leave Germany. They fled to Amsterdam to reunite with Justus, their elder son.

When Belgium and the Netherlands were occupied in May 1940, Felix was arrested in his apartment and, like all other aliens, taken to the Saint Cyprien camp in southern France. His interment there was a personal watershed; then Felix comprehended the true extent of mortal peril as a Jew under Nazi rule. He expressed this epiphany in his important work, The Camp Synagogue at St. Cyprien, 1941 - a unique work that symbolizes Felix’s realization that he belongs to the Jewish people and is so perceived by others. It was his first painting on a Jewish theme in many years.

In August 1940, in despair after three months of suffering under humiliating conditions in Saint Cyprien, Felix applied to return to Germany. When he reached the checkpoint at Bordeaux, he decided to escape by boarding a passenger train to Brussels, where he would be reunited with his beloved wife. From 1940 on, Felix Nussbaum lived in hiding with no source of livelihood. His Belgian friends met his needs and even provided him with a studio and art supplies. Lacking residency papers and in continual danger of being discovered, Felix moved from his hideout apartment to his studio and back, pursuing his artistic endeavors without respite. The themes of concern to him were fear, persecution, and the curse that loomed over the family’s members.

The fate of the expanded Nussbaum family was sealed. In August 1943, the protection given to employees of Justus Nussbaum’s scrap-metal business was revoked. Justus, his wife, their daughter Marianne, and the Nussbaum parents were arrested in their hideout apartments and sent to Westerbork. Half a year later, on February 8, 1944, Philip and Rachel Nussbaum, the artist’s parents, were deported from Westerbork to Auschwitz.

On 20 July 1944, Felix and Felka were arrested in their hideout and sent to Mechelen camp. Later that month they were deported to Auschwitz, where Felix Nussbaum was murdered on 9 August. His older brother, Justus Nussbaum, was transported from Westerbork to Auschwitz on September 3. Three days later, Herta, Felix’s sister-in-law, and Marianne, his niece, were murdered in Auschwitz. In late October 1944, Justus was sent to the Stutthof camp, where he died of exhaustion some two months later.

This chronology manifests the extirpation of one family that, despite years of flight, could not escape the long talons of the Nazi beast. Europe had become enemy territory. Nussbaum expressed the motif of dead end in an early work, European Vision - The Refugee, 1939. The Jewish refugee, holding his head in his hands, finds no shelter on the threatening globe, which stands on the table. The entrance to the room, wide open, provides no source of hope either. Symbols of extinction - a tree shedding its leaves and hovering ravens over a corpse - lurk outside. Seemingly, the artist already knew the final outcome, that no member of his family would survive the inferno. Felix endured for almost a full decade, against all odds, but he, too, was murdered a month before the liberation of Brussels. However, his works continue to tell his story, that of his family, and that of the fate of the Jewish people.

Yehudit Shendar, Senior Curator

Yad Vashem

Adolphe Nysenholc

Short film on Adolphe Nysehholc

His parents' Stolpersteine in Brussels

https://drive.google.com/open?id=19HbOIIu1Red84CJ6F9GwIFRQg0Kyzl6X

LE PAVÉ EN MÉMOIRE DE MALA-LEJA SUSSKIND A ÉTÉ POSÉ À ANVERS

Lundi 4 juin 2018 par Nicolas Zomersztajn

Un pavé de mémoire a été inauguré ce dimanche 3 juin à Anvers. Il s’agit du pavé de Mala-Leja Gutgold-Susskind, la mère de David et Tony Susskind.

© Regards

break

Ce pavé de mémoire (Stolperstein) a été posé à l’initiative de Tony Susskind-Weber, la fille cadette de Mala-Leja Gutgold-Susskind, qui s’est battue depuis des années pour qu’un pavé soit placé sur le trottoir devant leur ancien domicile familial situé au 167 Provinciestraat.

Tony et son frère aîné David (Suss), ont pu être sauvés grâce au courage et à la détermination de leur mère. Ayant tous échappé à la rafle anversoise du 15 août 1942, ils ont tous les trois été marqués par la brutalité et les violences des Allemands et des policiers anversois. Mala-Leja Susskind a donc décidé de vendre le peu de biens qu’elle possède pour mettre ses enfants à l’abri.

Péniblement, elle réunit la somme pour uniquement deux passages clandestins vers la Suisse. Elle organise alors le voyage de ses deux enfants qu’elle compte rejoindre lorsqu’elle trouvera l’argent nécessaire.

Ses derniers mots pour son fils David seront les suivants : « Zei a Mentsh, Douvid » (Sois un mensch David). Quant à sa sœur Tony, il n’y aura pas un jour qui passe sans qu’elle ne revive cette effroyable séparation. « J’aurais dû empêcher que nous soyons séparés d’elle », ressasse Tony Susskind lors de la pose du pavé.

Réfugiée chez une femme qui l’emploie, Mala-Leja Susskind continue malgré tout de se rendre à son ancien domicile pour nourrir un vieux monsieur resté dans cette maison. Mala-Leja Susskind-Gutgold y sera arrêtée le 6 octobre 1942 à Anvers et déportée de Malines vers Auschwitz-Birkenau le 10 octobre 1942 où elle sera assassinée.

Le pavé de Mala-Leja Gutgold-Susskind a été posé ce dimanche 3 juin 2018 en présence de sa famille et d’amis venus soutenir Tony dans cet hommage qu’elle a toujours voulu rendre à sa mère.

Après une prise de parole d’une représentante de l’Association pour la Mémoire de la Shoah (AMS), Menia Goldstein, président du CCLJ, a rappelé à quel point cette période a été cruciale pour les engagements et les combats futurs de David Susskind en tant que Juif et en tant que dirigeant communautaire.

La cérémonie s’est terminée par quelques mots prononcés par Tony-Susskind-Weber. Pour honorer la mémoire de sa mère, elle a déclamé El Male Rahamim, la prière pour les morts dans sa version pour les victimes de la Shoah.

Comme les deux premiers pavés anversois inaugurés le 11 février dernier, le pavé de Mala-Leja Gutgold-Susskind a été posé sans l'autorisation des autorités communales.

Source URL: http://www.cclj.be/node/11642

History of the project

20 years of 'Stolpersteine'

The artist Gunter Demnig has placed almost 60,000 "Stolpersteine" cobblestones across Europe. The first 50 were placed in Berlin in May 1996. Illegally. Now, it is the biggest decentralized monument in the world.

It was a beautiful sunny day in central Berlin, right in the former Scheunenviertel, which once housed a sizable Jewish population, predominantly from Eastern and Central Europe. An eclectic group had gathered - men and women, elderly and young, from Germany, Israel, the Netherlands, Canada (students on a Holocaust-study tour) and elsewhere. There was some apprehension; it was a somber occasion.

Wearing his trademark hat, Gunter Demnig arrived. He was laden with buckets of cement, his tools and two brand new, shiny Stolpersteine, commemorative stones, bearing the names Erzsebet and Jakob Honig. After a few brief introductions, he got down on his knees and started to dig a hole.

Behind the onlookers, children played in the vast, leafy empty space where once several buildings stood, housing dozens of families, many of which were forced out, perhaps later murdered in Auschwitz.

The artist was done in 10 minutes. Once the Stolpersteine were fitted snugly into the pavement, he polished them, took off his hat and got back into this van.

On the road much of the year

Gunter Demnig began his Stolperstein project in Berlin in 1996

In the evening, at a ceremony to mark 20 years of Stolpersteine - literally "stumbling stones" - Demnig said that he had placed the cobblestones at 17 Berlin addresses that day. This is not untypical for him. He calculated that last year he was on the road for 258 days, placing Stolpersteine in up to three villages, towns or cities a day, all over Europe.

Unimaginable in 1996, when he placed the first Stolpersteine in Berlin for 50 Jewish inhabitants of the district of Kreuzberg, as part of an artists' project examining Auschwitz. They were illegal then. There was no press, no police, no relatives, just a few curious onlookers.

Now, there are over 7,000 in the German capital alone and almost 60,000 across Europe, from Trondheim, Norway in the north to Thessaloniki, Greece in the south, Orel, Russia in the east and l'Aiguillon-sur-Mer, France in the west. They have become a familiar part of the landscape in Germany and the Netherlands. There are guided Stolperstein tours in Amsterdam, Budapest and Rome.

There are so many that Gunter Demnig no longer has time to both make and lay Stolpersteine. Since 2005, each Stolperstein has been made by hand by the sculptor Michael Friedrichs-Friedländer in his studio outside Berlin. He told DW that each is as moving as the next, but that he was particularly moved by 34 Stolpersteine he once made for 30 orphans and their four carers to be placed in front of an orphanage in Hamburg. "They were between three and five years old. I couldn't sleep for weeks."

Decentralized monument

Over 20 years, the Stolperstein project has become the largest decentralized monument in the world, a grassroots "social sculpture" that involves volunteers, students, schoolchildren and the relatives of Holocaust victims all over the world.

Contrary to popular belief, the Stolpersteine commemorate all victims of National Socialism, those who were murdered in Auschwitz and other camps of course, as well as those who survived, but also those who escaped them by fleeing to Palestine, the US or elsewhere.

Erzsebet's niece placed red roses on her relative's Stolpersteine

The large majority have been placed for Jewish victims, but they exist also for Roma and Sinti, for gays, for dissidents or people killed in mass euthanasia programs and for those whom the Nazis labeled "asocial".

Just this year, five Stolpersteine were placed on Berlin's central Alexanderplatz for five homeless people who were rounded up in the 1930s and sent to camps for "re-education" to become "worthy" members of society.

Reflecting the present

Stolpersteine are thus a way of showing the diversity of inhabitants in Germany before 1933 and paying homage to those who disappeared by returning their names to the places in which they led their lives. But, of course, they are also about the present. If you bow down to read the inscription of a Stolperstein, you quickly start thinking: That person was my age when he was murdered or the age of my daughter, or born the same year as my grandmother. You start to reflect, you start to wonder what would have happened to you, what would you have done if you had noticed that the family in the opposite flat had disappeared in the middle of the night. What would you do today if your neighbors disappeared? They are a way of making unfathomable figures fathomable, they are a way of making cold facts personal.

After Gunter Demnig had left the group in central Berlin, an elderly lady stepped forward to place a bunch of red roses on the two Stolpersteine. Then she talked about Erzsebet and Jakob Honig for whom they had been placed. Erzsebet was her aunt but they never met - what little she knew she gleaned from her aging mother.

Born in Budapest in 1896, Erzsebet divorced her husband one year after giving birth to a daughter. She went to Berlin in search of a job, leaving the child with her parents. She became a hairdresser and met Jakob. "They were in love." They married and once they had settled, Erzsebet's daughter was able to come from Budapest. She was sent to Palestine for her safety when the Nazis came to power. She was 16 years old. One of her sons came from Israel for the laying ceremony. He said that seeing the Stolpersteine being lowered into the ground was an incredibly moving moment.

It is unclear what happened to Erzsebet and Jakob. Their German inscriptions read "Schicksal Unbekannt" - "Fate Unknown".

http://www.dw.com/en/20-years-of-stolpersteine/a-19252785

https://memoireshoah.org/

In Belgium, the organisation 'Association pour la Mémoire de la Shoah' has been instrumental in the laying of Stolpersteine/ Pavés de mémoire. The first stones were laid in 2009 and since then over 300 have been placed around Belgium. The largest number are to be found in Brussels, however, there are also stolpersteine to be found in other cities such as Liège. The first Stolpersteine were laid earlier this year in Antwerp.

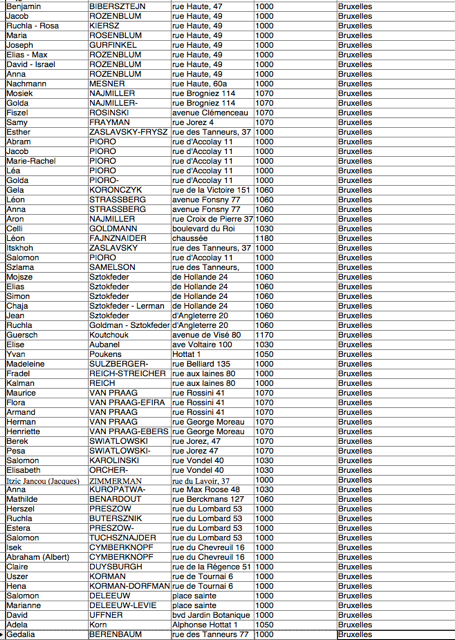

Names and locations of Stolpersteine in Brussels.

Comments

Post a Comment